Spaghetti Dinner at Tontitown Grape Festival

Stomping Grounds: A History of the Tontitown Grape Festival

Inch by inch, row by row,

Gonna make this garden grow.

Gonna mulch it deep and low,

Gonna make it fertile ground.

Inch by inch, row by row,

Please bless these seeds I sow.

Please keep them safe below

'Til the rain comes tumbling down.

Pullin' weeds and pickin' stones,

We are made of dreams and bones

Need spot to call my own

Cause the time is close at hand.

Grain for grain, sun and rain

I'll find my way in nature's chain

Tune my body and my brain

To the music of the land.

Plant your rows short or long,

Seasoned with a prayer and song

Mother earth will make you strong

If you give her love and care.

Old crow watches from a tree

Got his hungry eye on me

In my garden I'm as free

As that feathered thief up there.

– "The Garden Song," as sung by Pete Seeger

David Mallett, 1975

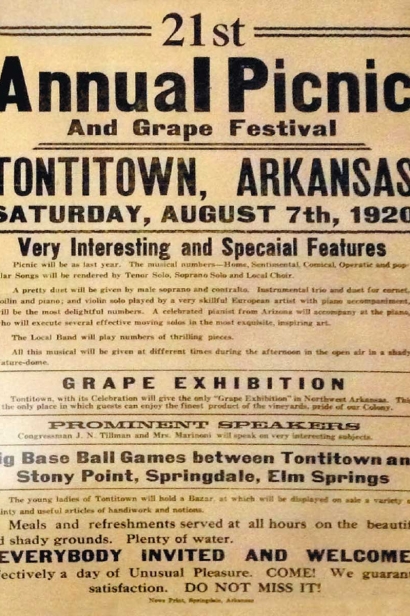

Traditions run deep in Tontitown, and the annual Tontitown Grape Festival is no exception. Now in its 116th year, the festival is held each year in celebration of the Italian heritage of this community. Planned for Aug. 5-9, this year's event will feature fried chicken and spaghetti dinners, carnival rides, arts and crafts booths, live music, and the crowning of Queen Concordia. This festival is thought to be the longest-running annual community celebration in Arkansas.

Heather Peachee, 33, has been involved with the festival much of her life, as her family supplies the grapes for the event. Her father, Chris Ranalli, along with his brothers, Norbert and Paul, still run the original family farm. They split the duties, with Chris Ranalli handling many of the row crops – grapes, tomatoes, peppers – and operating the Ranalli Farms Produce Market. Norbert handles farm equipment sales, and Paul manages the feed store.

The family has grown grapes for the festival since 1923, when Peachee's great-grandfather, Nazzareno Ranalli, originally bought the family farm. "They're really the last ones growing grapes," other than a few hobby vineyards, she says.

The Ranalli family has 18 acres of grapes, and the majority of the vines are populated with Concords. Other varieties include Fredonia, Reliance, Jupiter, and Mars, some of them developed at the University of Arkansas. In recent years, her dad started experimenting with Muscadines.

Milder summer weather makes the grapes slower to ripen. And, some years, like this one, the grape festival happens earlier in the growing season. "Sometimes we literally just started picking the day before the festival just because we had to wait as late as we could for them to ripen," Peachee says.

The same group of hired pickers have worked the harvest since she was a child. Peachee and her older sister, Summer Ranalli, spent a lot of time in the vineyards, picking grapes and keeping count of the boxes. The pickers would set the boxes under the leaves of the plants to keep them cooler, and the girls helped their dad gather them using a three-wheeler with a trailer.

The grapes available at the time of the festival are sold at the Ranallis' tent in quarts and half bushels, and staffing the stand was always a family effort with her dad and her uncles. The grapes also are sold all season at their market, which they opened about 15 years ago. Before that, the family sold all their grapes at the Fayetteville Farmers' Market. At the festival, they also donate the grapes used for the grape stomp and the ones served with the dinners in the parish hall.

TOWN'S DEEP ROOTS

Tontitown was founded in 1898 by a group of Italian Catholic immigrants led by Father Pietro Bandini. Their path to northwest Arkansas was winding and traumatic. They first came to Sunnyside Plantation in the southeast Arkansas Delta in 1895, to work for plantation owner Austin Corbin. They faced a severe malaria epidemic and grew dissatisfied with their living conditions, leading them to set out for northwest Arkansas, in a spot Bandini had previously discovered. Bandini named the community Tontitown after the Italian explorer Henri de Tonti.

At the end of June 1898, once they had cleared land and planted gardens, orchards and vineyards, the settlers held a thanksgiving picnic in observance of the Feast of St. Peter, Father Bandini's patron saint. This celebration continued annually by the Catholic families of Tontitown, and, eventually, an invitation to join the festivities was extended to the surrounding communities.

In 1913, the picnic was moved to August to coincide with the grape harvest, and it was called Grape Day. Tontitown farmers had become well-known for their vineyards, and specifically the Concord grape. Within a few years, Grape Day became the Grape Festival, which also served as a fundraiser for the local parish, St. Joseph's Catholic Church. In the 1930s, that festival started to look more like it does today, and it was expanded from one day to several.

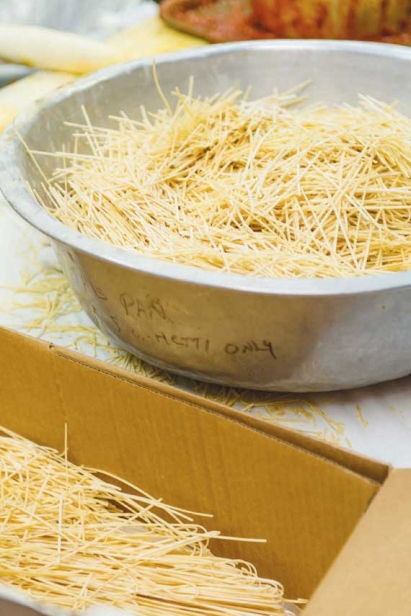

The core of the festival remains the spaghetti dinners prepared by church members. With preparations beginning in July, volunteers make hundreds of pounds of homemade pasta and sauce for dinners that will serve thousands of festival-goers, about 9,000 in recent years.

As teenagers in the late 1990s, both Peachee and her sister unsuccessfully competed for the title of Queen Concordia, an annual tradition since 1942. The competition is based on selling the most raffle tickets for a new car or truck.

As a child, Peachee went with her mother and stepfather to a Protestant church in Springdale, but she remained connected to St. Joseph's church. Her aunt Agatha, the second oldest of seven children, made sure all the nieces were signed up to work in the parish hall during the festival.

Even as Tontitown has grown, the festival continues to be a collaborative event put on by the families there. It also brings everyone together each year. "People who've moved away, they'll come back for the grape festival," Peachee says. "It is kind of a reunion, a tradition."

"There aren't that many traditions out there that still continue, and I think it's a big deal to people. People who aren't even really connected, they still want to be a part of it," she says.

Peachee also learned cooking techniques and recipes from her aunt Agatha, who always makes spaghetti and rolls for family get-togethers. The aunt also does the baking for Ranalli Farms market, and she makes and sells dried pasta there. So, Peachee grew up loving to cook. Her lasagna, with lots of garlic and a little sugar in the sauce, is her specialty – and her dad's favorite.

Her great-grandfather, who came to United States in 1907 and then bought his farm in 1923, also passed down the art of winemaking through the generations. In addition to the farming tradition, Peachee, with her husband, David, now owns and operates the Tontitown Winery, which opened in 2010 and is one of eight wineries in the state. It's housed in the old Taldo House, which was built in 1917, and the space was the former home of the Dixie Pride Bonded Winery No. 40, meaning it was the 40th winery in the nation established after prohibition ended.

Peachee also joined the Tontitown Historical Museum board about five years ago, at her father's suggestion, and now serves as board president. Having grown up working in the vineyards and now with the family winery, she feels she is able to be more active about carrying on family and community traditions. "We've really tried to keep our traditions and our stories alive," she says. "We've got to keep carrying on, so our kids know where they come from."

The museum, which is funded by the city and donations, houses numerous artifacts with stories behind them: bocce balls, a wedding dress, a stained-glass window from the first church built, Father Bandini's secretary desk, pasta-making equipment, and many old photographs. For the first time last year, the museum stayed opened on the weekends through the winter months.

The museum also hosts two major community events each year. Each May, Heritage Day is held at Harry Sbanatto Park, and each November, a reunion and polenta smear is held at the church's parish hall. A main goal at the polenta smear is to collect and identify historic photographs. Museum board members share those collected images in Facebook posts and an email listserv (called Tontitown Stories). That initiative, along with the museum's quarterly newsletter (The Tontitown Storia), recently won the Award of Outstanding Achievement in Media from the Arkansas Museums Association.

EARLY INTEREST

When Susan Young was growing up in Fayetteville, on the rare occasions that her family dined out, they sometimes went to the Venesian Inn in Tontitown. That was literally her first taste of the town, and she fell in love. It wasn't until college that she first attended the annual grape festival.

Young, now outreach coordinator at the Shiloh Museum of Ozark History in Springdale, has made her living researching, chronicling, and educating others about local history. At the request of the Tontitown museum board, Young wrote one book, So Big, This Little Place: The Founding of Tontitown, Arkansas, 1898-1917 (2009), with all proceeds going to the Tontitown museum.

Young says that the Ozarks weren't historically a place of diversity when it came to the places from which people had moved. Tontitown started with the priest, Father Bandini, and about 40 families who came here as a unit in 1898. She is most impressed with the strength of the family connections, both nuclear and extended families, and how those have endured for more than a century.

Many pioneer settlements in the Ozarks had a church at the heart of the community, even if not everyone in the community attended. Springdale, for instance, grew out of the Primitive Baptist Church, established in 1840 in the community originally called Shiloh. In other small communities, some of those churches have long since faded. But, in Tontitown, the very church at the core of its foundation is still going strong and thriving. The church is the major driver behind the community tradition of the grape festival.

"To have this Italian story, it just brings a richness to our local history," Young says.

Bandini had a vision of taking people who were farmers by trade and putting them on farmland in middle America. Their way of farming in northern and central Italy was much like the farmers in the Ozarks. Families ran small farms that fed and sustained themselves. When talking about those aspects of self-sufficiency, a strong work ethic, and the ability to adapt in less than ideal conditions, "you could be talking about an Italian family that came here from Italy or an Ozark family that came here from east Tennessee," Young says.

The community quickly established itself in the region, despite a prejudice against Catholics at the end of the 1800s and in the early 1900s. "The work ethic of the people and the leadership of Father Bandini went a long way toward helping the community establish itself in the eyes of old-timers," Young says.

FARMING SUCCESS

Rebecca Howard's great-grandfather, Silvio Pianalto, was an early settler of Tontitown. As a child of 8 or 9, he came with his family to Sunnyside. After his father died in a sawmill accident in Sunnyside, his mother married a Berucchi, and the family moved to Tontitown. Three of his father's brothers also came to Tontitown; the four brothers hailed from Valli del Pasubio, in Veneto, Italy.

Howard, 36, is a doctoral candidate in the history department at the University of Arkansas and also serves on the Tontitown museum's board. She says the Italian families came to Sunnyside for land, which they didn't have access to in Italy, where they were tenant farmers.

Bandini was involved with an immigration society in New York, and knew Corbin, the plantation owner, before he started this project. Bandini had developed this idea that immigrants coming to large cities was the wrong way to do this. They were living in tenements, were not assimilating, and were not any better off than they had been in Italy. "To truly be successful in the United States, they need to do what they were doing back in Italy, which is farming," Howard says. Corbin, acting as a philanthropist, wanted to help with that cause and also needed farm workers at a time when blacks were leaving the rural south for northern cities.

Howard, who grew up on a chicken farm west of Cave Springs, attended a Catholic church in Bentonville rather than the Tontitown parish. Still, she recalls her mother helping to make the pasta from scratch for the grape festival, with all the volunteers using their own pasta machines and hanging the fresh strands of spaghetti on rows and rows of drying racks in the parish hall. She and other children would play on the playground outside. "You'd get in a ton of trouble if you'd run through them, as a kid, while they were drying," she recalls, giggling.

She says that her grandmother's lasagna and ravioli were staples at family holiday meals. Her mom and grandmother would get together to make ravioli, spaghetti, and lasagna noodles, plus the sauce, and then they took it all home in plastic storage containers to freeze it.

The festival survived the Depression and World War II because the Welch's company got involved as a sponsor of the event, Howard says. The festival continues to be a major fundraiser for St. Joseph's church, which keeps some of the money and sends some to the Diocese of Little Rock.

Howard is interested in making the record of Tontitown's history as complete as possible. "I think part of it's just how I'm wired, like there are parts of it that are a mystery," she says. "I'm fascinated by this contrast between my family's oral history and what we can find in documents. And how accurate, actually, the family oral history has been. A lot of it's really good."

PRESERVING TRADITION

After that first book, Young agreed to help the museum with another. The museum's board members had started their annual polenta smear, another community event centered on food traditions, as well as an oral history project. Between 2002 and 2005, volunteers conducted 48 interviews with Tontitown residents who ranged in age from 56 to 93, most in their late 70s and early 80s, as they talked about what it was like to grow up in the Ozarks in the early 1900s. All of those interviews were transcribed, and then Young helped shape those into a readable book format, editing Memories I Can't Let Go Of: Life Stories from Tontitown, Arkansas (2012).

"This is a great example of a community collecting its own history," Young says.

Still, the long-running grape festival may be the most obvious example of how much this town values tradition. Each year, with this event, it continues to celebrate its roots, and its strong ties to family and church, unique aspects that make Tontitown special.

"I will go on a hot evening in August and stand in line for an hour to eat fried chicken and spaghetti, mainly because it's something that people have been doing for over 100 years," Young says. "For someone who loves and appreciates tradition like me, that's golden."