Water from a Tree: Making Maple Syrup in the Ozarks

Canada has the maple leaf on its flag. Thoughts of Vermont conjure cozy images of buckets on trees and snow on the ground. New York even has a research forest, where Ivy League students can study the sugar maple. They all have the right species of tree plus the right weather, and so the northeastern United States and Canada provide the entire rest of the planet with the unique sweet golden flavor of maple syrup. It turns out, though, that the Ozarks are just far enough north to have some of the right trees and some of the right weather for tapping and making maple syrup.

Although research articles and books from other parts of the country refer to the sugary liquid that begins to rise in the trees in late winter as sap, Misty Langdon, of Our Green Acre Farm, is firm that the real Ozark word is water. Her family, six generations and more, has farmed, hunted, owned, and tromped their land in the Ponca Wilderness where Steel Creek joins the Buffalo River since long before the idea of a National River was a twinkle in anyone's eye. In days past, one branch of the family planted sorghum, that traditional Southern sweetener that grows as a grass all summer until it's taller than everyone. It is cut and pressed, the green juice squeezed from the stems and boiled down to sorghum molasses in the fall. But on another branch of the family tree, they took to the woods in winter.

Sugar maples (Acer saccharrum) are traditionally used for syrup because they produce a lot of sap when tapped, and that sap is sweet, about 2 percent sugar. For a few lucky landowners, scattered sugar maples, sometimes called hard maples, can be found in the hills and hollers of the northern part of our state. There are, however, other species that can be tapped and still taste good. In the same genus as sugar maples, silver maples (Acer saccharinum) are planted as fast-growing shade trees and red maple (Acer rubrum) and box elder (Acer negundo) are natives to Arkansas. These other species yield less sap and it is less sweet so there is less finished syrup, but they could be a source for homegrown suburban sweetener. Beyond maples, some syrup makers even tap unrelated trees such as birch and walnut, as well as a few others.

Even without their leaves in the grey month of January, a child could spot the sugar maples on Langdon's family property. Particularly a child, that is, because the distinctive round scars of each year's tap are low down on the trunk. There are trees known in New England that have been tapped for a hundred years, and Langdon points out that it's like looking back in time to see the taps made by her great-grandparents, her grandparents, and her father, Loyal Breedlove. Stored up in the barn, Breedlove still has the hand-held bit and brace and a hand-carved elderberry spout used by some of those past generations, but he prefers a cordless drill and short lengths of pipe for his visits to the trees.

A tree of size to be tapped is at least 10 inches in diameter at chest height (or 31 inches all the way around) and a tree larger than 18 inches in diameter can support two taps. A few supplies are needed: a drill, a spout, and a container. Holes are drilled about two inches deep into the wood at about three feet up from the ground on the sunny side of the tree, with a slight upward tilt so that sap will flow down and out. Breedlove uses a 9/16 inch drill bit and 1/2 inch CPVC pipe. Traditional metal spiles for holding buckets are 7/16 inch, although newer ones tend to be smaller. The best container for catching the sap is at least a gallon and enclosed to keep out rain, bark, and bugs. Although those metal buckets in Vermont are picturesque, a clean plastic milk jug works just as well. Besides, the commercial producers of maple syrup don't use buckets anymore either. Their sugarbushes are complex miles of plastic tubing through the forest.

The time to tap in the Ozarks is probably late January and into February, but it is a matter of watching for a stretch of the right type of weather. Sap will not flow every day, but only when conditions are right. Langdon advises, "the season begins when the trees freeze at night and thaw during the day." If tapping starts too early, the holes may dry out or heal before yielding much water. If the trees are tapped too late, they will bud out with the onset of warmer weather, giving the sap off-flavors and making it unusable. This arrival of warm weather is one of the challenges of producing syrup in Arkansas. Spring arrives faster here than farther north, and that leaves a brief window of time to collect water for syrup.

The gallon jugs hung on trees have to be attended to daily or nearly so, since some trees give more sap, or a jug may get knocked off a tree. Unlike in agriculture where plants are grown where the farmer chooses, gathering sap from maples is working in and with nature, in mid-winter no less. The maples grow where they grow, and if that is uphill and a half-mile from a road then the hopeful syrup maker simply has farther to walk.

The great-great-grandfather of Langdon's father made syrup. A few members of the family would travel out with a wagonload of supplies, deep into the woods near Parthenon where the maple trees were thick, and would stay for two to three weeks until the job of tapping, collecting, and boiling down was done. Breedlove himself remembers even his older brothers getting to go camp out, but they stopped before he was old enough to join them. "There were more trees then, most of them have been cut out," he said. His wife and Langdon's mother, Charlene (Villines) Breedlove, also grew up making syrup with her own grandmother, though they would walk to the woods near Steel Creek and harvest and cook down the water there. For a family together, satisfying their sweet tooth for the coming year, "It was," Langdon recalls, "always a gathering event." She added, "Tapping is just tradition, it was a way for folks who couldn't always find a bee tree to have syrup and sugar. Poor man's sugar – but what a luxury it is now!"

Though it may vary slightly from location to location and tree to tree, it takes about 43 gallons of sugar maple water to produce a gallon of finished syrup. So, if seeing the sap start to flow from the spout is the moment filled with possibility and anticipation, then the boiling down is the reckoning and realization that 42 of those gallons are unwanted steam. Boiling, or using reverse osmosis as some commercial producers do, is to concentrate the sugar, raising it from a nearly undetectable-to-the-tongue 2 percent in the water as it comes out of the tree to 66 percent in the delicious finished syrup. As the sugar concentration rises, so does the boiling point, so that the syrup boils at 7.1°F above the boiling point of water when it is finally ready. Reduced even further, ever so carefully heated to 234°F, the syrup will crystallize into sugar. "One of the most treasured things we do is cook the syrup down to sugar," says Langdon. "You just keep cooking and cooking and after what seems an eternity it will cook down to a brown sugar consistency. The product is amazing and, because of the long time to produce it, is considered precious."

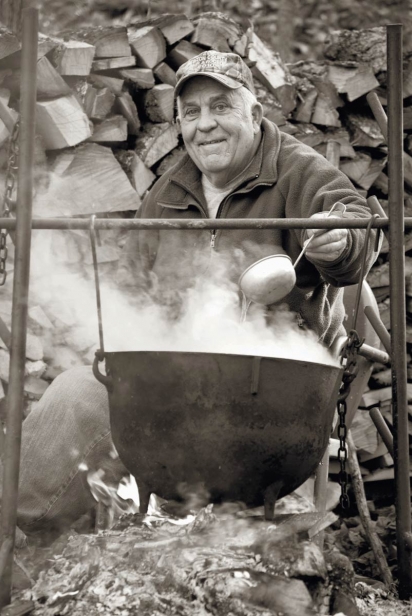

The initial cooking of the sap or water is usually done outside, due in part to the copious steam produced. Although official sugar houses use custom, wide and shallow evaporator pans, Langdon's family has used the same black cast iron pot, suspended over a wood fire, for generations. "I can remember being bundled up (it's generally very cold during maple season) and I don't think I was over three years old. I loved sitting by the fire, and as I got older, just a couple years older, I got to help stir. As a kid, stirring a huge kettle that is sitting on a fire is awesome!" The children were warned not to poke the fire as ash would rise in the air and land in the syrup, something not approved of by the grandmothers. Finally, as the water reduces, it is brought inside for closer watch. Charlene Breedlove places full pots on top of her woodstove, which is already cranking to warm the house in January. As a bonus, the heat gently simmers the maple sap until there is less and less and it becomes sweeter and sweeter, an alchemy of water from a tree becoming a year's worth of golden syrup for an Ozarkansan family.