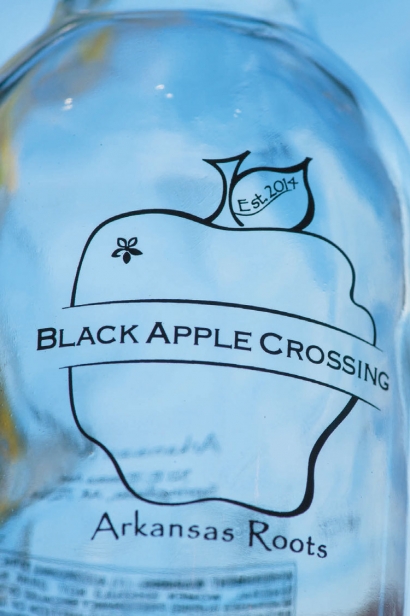

Black Apple Crossing: Springdale Opens Arkansas’ First Cidery

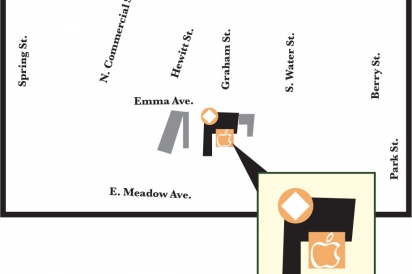

When I arrived at Emma Avenue in downtown Springdale, guided by Siri, my phone’s navigation system, I was confused. In search of Arkansas-made hard cider, I only found an unoccupied storefront. It took following the hum of happy conversation to locate the discreet, off-street entrance of Black Apple Crossing taproom.

I claimed a space at the crowded wooden bar, and, finally, I was sipping an Arkansas hard cider. That first, tart, refreshing taste was something I had been anticipating for years.

Anyone who has listened to the food stories of Ozarkansas knows that we are famous for apples – with Benton and Washington counties at one time growing more than anywhere else in the country. Making cider, hard cider specifically, makes so much sense in celebrating that part of our story. And as Ozarkansas has slowly shaken off the hangover of Prohibition-era blue laws and plunged into the craft beer revolution, the revival of cider seemed inevitable. Black Apple Crossing opened in July 2015, and Leo Orpin, John Handley, and Trey Holt are making hard cider in Ozarkansas. Finally.

Hard cider in America

Early American settlers adapted hard cider to every occasion – spiced and hot in the winter, concentrated by freezing into something more potent, and with Scottish immigration, the expertise to distill hard cider into apple brandy. Laird & Company in New Jersey, colonial America’s first distillery, produced spirits from apples as early as 1698. Then came Prohibition, and both the trees and tradition of hard cider making were lost. By the time of repeal, American tastes had turned toward beer and spirits such as gin and whiskey.

Origins of Black Apple Crossing

The three friends were concerned about wading into a market approaching saturation. As they talked through plans with the friends who had lifted many glasses of Leo and Trey’s handiwork, they kept hearing: “Your ciders are fantastic; why not do that?”

“We were nervous,” Leo says. “We thought, ‘How come nobody else has done this?’”

But, the more they explored the idea, the more they loved it. Cider felt like something that belonged here, an important part of the story of this region that had been neglected, and something that stirs a happy sense of nostalgia for the people who taste it. Once they settled on cider, they began to move forward in earnest. It was time to find a home for this project.

“It was November of 2013, [and] we looked at this building the first time,” John recalls. “We saw the potential, but we were skeptical because of the age.”

“It was the George’s hatchery in 1935,” Leo says, “and every decade since then someone added a layer of stuff to the building. I think it was the 12th time we looked at when we said, ‘Okay, let’s do this.’ There may have been some sampling of cider involved in that decision.”

The initial plan had been to focus on producing cider for regional distribution. But their building had become an important part of their story; it felt perfect for a taproom. The taproom gave them a more direct relationship with their local market, and they could gauge the reaction from guests and refine recipes.

“We could get people to try all these craft ciders,” John says. “We had like 40 recipes to start out with. What better way to put those out there? Put them in the taproom, be seasonal.”

After months of tearing down, cleaning, and building out, they were finally ready to open in July of 2015. “We felt like we were trying to push an elephant up a hill,” John says. “But finally we got there, and then gravity took over.”

People behind the production

“We get in tight spots keeping up with production,” Trey says. “But I just love doing this.”

When asked about formulating recipes, Trey says that process happens in his mind. “Whenever I go to a natural food store or a spice shop, I’m tasting raw spices and teas. I’ve got this bank in my head of ideas I want to try.”

The ciders rotate with the seasons and with Trey and John’s inspiration. The flagship cider is Dry Guy, lean and elegant with a champagne-like crispness. New ciders roll out at the taproom every week. It takes about 10 weeks for a cider to go through complete fermentation and be ready to serve, and new experimental ciders Hop-full and Gingersnap should be ready to sample in December.

Springdale has embraced their new community space. In spite of a location that takes good directions to discover, the taproom is full every night they are open, and food trucks and bands complete the experience.

“It’s like the watering hole down here – kind of like the English pub style,” Trey says. “Everyone just goes and hangs out like a local backyard.”

Heritage for the future

Apples are so much a part of the agricultural history of Ozarkansas, but the reality is that they aren’t much a part of the present. Black Apple Crossing has been pursuing local sourcing, but the apples just aren’t here right now. Most of the historic orchards have been bulldozed for pastures and chicken houses or sold for development. So the apples are currently sourced mostly from Washington.

“We buy a blend for cider: dessert apples, semisweet for balance, bittering apples for tannins. All of it cold pressed, sent to us in less than three days, and we start fermentation the day we get it,” Trey says.

“People offer to sell us a few bushels of apples,” Leo says, “but we need thousands of pounds.”

John estimates that it will take about 500,000 pounds a year just to keep up with current production.

That is the reality of the gap between the history of apple growing that is part of the region’s very identity and the current limited production of apples in Ozarkansas. To change it will require consistent, volume buyers who can make new orchard planting a worthwhile endeavor.

Wendell Berry said: “Eating is an agricultural act.” And drinking clearly is, as well.

“It’s three years to get orchards producing,” Trey says. “But that’s what we want to bring back. We’re trying to work with people – we tell them we’ll buy whatever they can grow for us. I grew up in south Arkansas; my family farmed. I’d love to do that. But somebody will. Somebody is going to be able to live on their orchard.”

“We’re at the beginning of a new movement,” John says. “We have the appropriate climate, where we can be more like a winery, vertically integrating the growing, making contracts with local orchards, pressing our own juice, and eventually planting our own.”

“It just makes me excited for the future,” Leo says.

It has been almost 100 years in the making, but Black Apple Crossing is finally reclaiming an important, delicious part of the region’s identity and landscape. And that is worth raising a glass to.

321 E. Emma Ave., Springdale

Open seven nights a week

Try this at home

Want to see how easy it is to make your own hard cider? Buy a gallon of fresh-pressed, unfiltered, and unpasteurized cider with no preservatives. (It will be found in the refrigerated cases of the grocery store.) Open it, and let it sit on your countertop at room temperature for two weeks with the top loosely covered. The naturally occurring yeasts will turn your cider “hard.” When you smell your finished cider, it should smell fresh and a little yeasty. Reseal it, and then chill for a few weeks to let the sediment settle.

Enjoy!

Assist Siri

If you rely exclusively on your navigational system to determine the location of Black Apple Crossing, you may be confused once you have “arrived” at the destination.

Black Apple Crossing

321 E. Emma Ave.

Springdale, AR 72764

Where a GPS will likely send you

{The “front” of the business, but you can’t get in here.}

Black Apple Crossing

{The “secret cider hideout.”}

A red brick building

{Good luck!}