For the Love of Smoking & Curing

char • cu • te • rie: noun, (,)shär-1 kü-tǝ-1 rē

1) a delicatessen specializing in dressed meats and meat dishes

2) the products sold in such a shop

It was a mission inspired by charcuterie.

With only two hours of sleep after a hectic night in my restaurant, I was squeezing seconds out of the curves of Arkansas 59, trying not to be any later than could be called polite for my meeting with Susan Tucker and Jason Haid, owner and executive chef/ owner (and mother/son team) of River City Deli on Rogers Avenue in Fort Smith.

Chef Jason and Susan invited me in to their bright, welcoming dining room. I sat down with Jason over coffee to talk charcuterie specifically, but also restaurant philosophy, what it means to be a deli, and good tomatoes.

It immediately became clear: Chef Jason is a kindred spirit – the best sort of people in this business. He's one of the crazy ones, who dabbled in the restaurant business, and then just couldn't shake it. They do this work for love first, and for money at a distant second. He's among those talented enough to do anything they want, and what they want is to make great food for their communities.

Casey Letellier: Tell me about the corned beef and pastrami you are famous for?

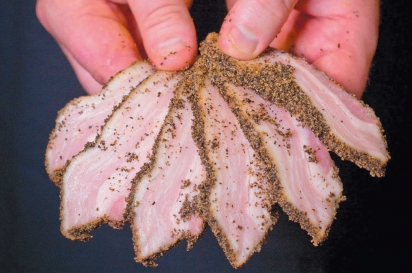

Jason Haid: Corned beef and pastrami are both brisket. It's a 14-day minimum for the corned beef we use. We get it in a raw state. We take it; we season it; we cook it. Pastrami is a 14-day to 28-day process, with peppers and spices and pickling spices. We use a wet cure. The pastrami is from the deckle, the fattier part of the brisket. A rich, unctuous, melt-in-your-mouth kind of thing. That's where it is – fat is flavor!

When you braise that over a long period of time, letting all that fat melt into the meat, you cut into it, and it's juicy, salty, peppery – it's a perfect meat. When it comes to the preparation process, why you're doing what you're doing, it's perfect.

Historically, that kind of salt cure for corned beef and pastrami for the brisket was just to preserve meats. These were throwaway cuts. The butchers were selling prime cuts – filets, ribeyes, that sort of thing. It was a different time; they didn't have refrigeration. They had to figure out something to do with these leftover cuts.

CL: What makes you a New York-style deli?

JH: We call ourselves a New York-style deli. Which is true and not so true. We did ourselves a disservice to call ourselves a deli because we are so versatile. While we have amazing sandwiches, cured and smoked meat, we also have soups, entrees, and this Hungarian-stuffed cabbage – my great grandmother's recipe. Ninety percent of everything we serve we make in-house. We do a fine dining night every month: seared duck breast, seasonal fish, local veggies. And that has led into high-end catering events around town that have nothing to do with deli food.

CL: Do you ever bring charcuterie into your special events?

JH: I did these duck confit wontons for one event. We got whole, organic, free-range ducks, rendered down the fat (there is nothing better than duck fat!), added a lot of roasted garlic, fresh thyme, rosemary, then put all of these pieces together, covered it with the fat, and let it sit for about 18 days. (Though that can preserve 60, 70 days.) We shredded the meat, rolled it into wontons, and made this sauce with hoisin, soy and ginger; that was it. We had my guys in the back, all my front of house people as well, until midnight the night before the event rolling wontons.

CL: So, if you're not exactly a deli . . .

JH: We're fighting our own marketing. It says on the back of our shirts, 'more than just a deli.' We ask once a week: what are we? It comes from trying all these things. But our market knows what we are – and likes us.

Fort Smith most definitely likes River City Deli. Efortsmith.com, which conducts an annual reader's poll, awarded them best overall restaurant and best caterer their first year. This year, they also were recognized for best desserts.

Chef Jason and Susan sent me out the door with one of their pastrami sandwiches, almost too big to handle behind the wheel. It was luscious and satisfying, with the concentrated salty essence of beef.

***

My conversation with Chef Rob Nelson from Tusk & Trotter American Brasserie in Bentonville was planned for later that afternoon. So I headed back north, this time up Interstate 49, with a stop in Johnson at James at the Mill to grab a few boxes of Bibb lettuce, then a quick drop off at 28 Springs [in Siloam Springs], more coffee, and on over to downtown Bentonville.

Tusk & Trotter is the living room of the Bentonville food scene. Hang around with Scott Baker at the bar and order a pint of Ozark Pale Ale, and eventually you'll see everyone who runs or works in restaurants or is just passionate about food. This is the axle. Everything turns around this ambitious little restaurant.

Chef Rob has been at the forefront of the food scene renaissance in this part of Ozarkansas. I love his food, and I was so excited to bask in some of his genius. He is this larger-than-life guy, with intense eyes that would be intimidating if he didn't smile so much. We sat in a booth in the dining room (next to a giant pig painted on the wall, labeled with different cuts) and talked charcuterie.

CL: So how does charcuterie show up on your menu?

Rob Nelson: We cure our bacon in-house; we make our own terrines, patés, sausages. We're testing out dry hanging as well. We're getting the variances all in order with the health department to be able to hang meat legally, so we'll do guanciale, prosciutto, hams – things that focus on the pig. The pig is the backbone of our menu, and we try to utilize that in any way we can, from head cheese to curing the liver.

CL: How do you make bacon?

RN: For the curing process, we use sodium nitrate, which adds flavor and gives it that pink color. Our bacon is on cure a month, turned every other day. Then we rinse it, let it dry 24 hours, then smoke it to 155 degrees to be ready to go. We've got about 200 pounds of bacon under cure at any time.

CL: How does smoke contribute to charcuterie?

RN: Smoke is one of the oldest preserving agents. You smoke something, and you've got a two-week span without refrigeration. That and salt cure, things they used to do before refrigeration was possible to stretch out the life of whatever they were eating. That's kind of what we do here. We take old-school charcuterie and make it the focal point of the dish.

We use applewood for smoke. Since Benton County has been known for apples, we try to keep it with that flavor. We actually go out and get applewood and break it down ourselves.

CL: How does charcuterie fit into your bigger food philosophy?

RN: At Tusk & Trotter, we're snout to tail. I want to show the versatility of the pig by using old-school cooking technique, rather than just slapping it on the grill. Charcuterie is a way of not wasting the animal. Things like head cheese and paté, using organs and other things that would otherwise be thrown away. We make a pigtail soup, where we brine and braise pigtail and then fold that meat into our white bean pigtail soup. We try to have a zero waste sheet at the end of the day.

CL: Where do you source your animals?

RN: Our pigs come from Mason Creek Farm out of Fayetteville. (We've gone through 15 hogs this month. That's just pork.) Our lamb is from Ewe Bet Farm out of Cave Springs. For our beef, we use Creekstone Farms out of Arkansas City, Kansas, where they're grass-fed and then finished with grain. Our ducks come from the Bentonville Farmers Market when they have them. Looks like we're going to be able to start getting venison soon. It's just making relationships and keeping them.

CL: Clearly this whole process is at the heart of Tusk & Trotter. What makes it so exciting, and how did you get into this in the first place?

RN: Charcuterie is the purest form of cooking there is. It's a craft – an art. You can utilize the entire animal. You can store it for months at a time. You can feed a whole mass of people with just one animal. It's a process that let's you get more yield. It's just fascinating to me. I tasted dried chorizo in Provence – fig and walnut chorizo – and I was hooked. I was like, 'I need to know how to make this.'

This is new here. This is a renaissance – young people like us are bringing this back. You don't have to just stick with the old ways, but we can use those basics to build on. I wake up every day and I know exactly where my food is coming from, how those animals were treated, how those plants were raised. It's awesome. It's what keeps me going.

It's a contagious enthusiasm. Since talking to Jason and Rob, I've been reading Michael Ruhlman's Charcuterie. I'm buying pork belly from Roger and Jennifer at R Family Farms in Canehill this Saturday to try out Rob Nelson's bacon recipe. This means that, by the time you read this article nearly two months after it was written, I'll be inviting friends to join me for BLTs. We'll savor the last of the season's perfect tomatoes, the return of tender, cool-season greens, and bacon, made weeks ago in anticipation of this moment.

This runs contrary to the way I normally live. But, I'm trying to slow down, pay attention, unplug. I say that (and hear it said) all the time. Maybe this way of thinking about food is part of how that happens. Cooking that looks ahead, not to the meal "10 minutes or less!" from now, but to a meal still weeks away. Cooking filled with the kind of joy that is possible only with space and anticipation. Cooking that honors the animals we eat by using everything. A very slow, very patient revolution.